© 2006 Copyright of David E. Smith Publications

All Rights Reserved. Made in U.S.A.

Table of Contents

www.despub.com is undergoing a complete transformation in several stages. (1) Product listings are being updated continually. (2) A whole new engine will soon be driving it (even though the home page may tend to look familiar). (3) The number of items available for viewing will nearly double. (4) The Appendix information will be embedded in the listings (they are currently on the www.churchmusic.biz website.) (5) New sound files will be available. (6) Most impressive will be the vast number of search options which will be available whether searching for a product or a “Lines and Spaces ®” article.

Still existent will be the information that's been there before a listing of the many fine dealers who handle our product line, the newsletters and the exhibition list.

You might benefit by checking it now since it lists many conferences for the coming months and just might include a conference you wish to attend.

Many new DESPUB Catalog (Print or CD) items are now available. Check the websites or the displays at your favorite dealer.

First, for solos, there is a delightful arrangement of "Be Thou My Vision" by Wayne Fritchie with piano accompaniment for the following instruments- flute, oboe, clarinet, alto sax, tenor sax, and violin (each a little different in content, harmony, and key).

If you want something a little easier, see the well-received solo, “O Come, O Come Emmanuel” by Billy Madison. It's available for the various woodwind, brass and percussion instruments, while the string version is modified and edited by Robert Ewing, complete with bowings and other helpful information.

Brass duets are often not easy to find, but here are a few that are now available: "I Sing The Mighty Power of God," " And Can It Be," "A Shelter In The Time Of Storm," "Rejoice In The Lord," and a trio "Saviour, Like A Shepherd Lead Us." These are all arranged by Dana F. Everson. While they are basically for trumpet, trombone and piano, they also come with optional horn and baritone parts.

For larger works by Everson, there is Springs Of Living Waters for flute quartet; "Come, Ye Thankful People, Come," for trumpet quartet; "We're Marching To Zion" for woodwind quintet; and for brass quintet, "The Battle Of Jericho," and "The Steps Of A Good Man"-optionally a sextet also.

There's just about something for everyone. And if these aren't enough check out the other 5,000 pieces we have to offer. As Psalm 150 says, “Praise God with all kinds of instruments.”

The Valsalva Maneuver (VM), named for the Italian anatomist Maria Valsalva, is a respiratory action where a person attempts to blow out air against a closed mouth and nose. With the VM comes a dramatic increase in thoracic pressure and a corresponding reduction of blood flow into the thorax, especially in veins that lead to the right atrium of the heart.

Some of the benefits of VM include:

As wind, and particularly high brass, players, the VM is nothing but trouble. So, while there are important health benefits of the VM, when it comes to playing an instrument, the VM is a detriment. Creating inter-thoracic pressures through throat or epiglottal constrictions is the root of most tonal production and even articulation problems.

Blowing with even minimal compression in the thorax will result in reduced resonance. The player essentially works against himself by creating this isometric condition. The lips require a rich, quantitative supply of breath for maximum resonance. Compression reduces the lip's need for quantity dramatically much like kinking a water hose reduces the flow of water. Kinking a water hose may be good for your garden, but compressing breath will starve your tonal output. The resulting timbre, though intense, is thin, brittle, lacking in low and middle harmonics.

Using the VM while playing forces the lips to work more strenuously to compensate for the lack of quantitative support, so the player fatigues faster than in conditions of free-flowing breath. Lip slurs are more tiring. Initial attacks tend to be insecure and wider register shifts or intervals are ragged. And to add insult to this injury, pitch runs high, particularly as notes ascend. As notes get higher, the tongue has to inordinately rise in position to maintain airflow in this situation of decreased quantity.

Tonguing is similarly affected negatively. Clear, crisp articulation depends on adequate quantity of breath being dispensed to the lip. But the VM compression reduces quantity and forces the tongue to press harder against the lessened air flow, further compounding the weakened, tight tone and sharping of pitch.

In short, the VM inhibits full-bodied tone, endurance, secure pitch and articulation. What can save a player from this dilemma?

One challenge is that a player can't consciously stop the VM once it occurs. Once air compression has taken place in the breath, it can't be undone until another breath is taken. And the feeling of compression engages a bodily response of tightening the stomach and back muscles while the diaphragm contracts (i.e. trying to breathe in while blowing out). Sounds hard doesn't it? To compound this, when the player is nervous, or in an insecure situation, the breathing will likely become labored and restricted.

What follows are some general suggestions for replacing the VM habit with free-flowing breath. The online article listed (below) by Brad Howland details several helpful approaches and techniques in efficient wind respiration. Arnold Jacobs' thoughts on this subject are definitive, as found in the books listed at the end of this article.

• Think of breath as wind, flow of wind, not as air and definitely NOT as pressures.

• Begin with a relaxed, open inhalation, using an “oh” or “ah” vowel as you breathe in. Jacobs' direction for inhalation was “suck air AT the lips and make only the sound of wind.” This will go a long way to setting the blowing into relaxed, fluid motion. The model of a yawn or sigh is also an effective trigger for relaxed inhalation.

• Treat the blowing process as a single action: in and immediately blow out, NOT breathe in, compress, then blow. I like to think of this like a golf or baseball swing. Such swings are a single-action flow of movement. Wind playing is the same.

• Blow directly TO the lips. Jacobs would frequently have players put a sideways finger parallel to the lips and blow to the lips, stopping the air with the finger, then suddenly releasing the breath energy. In a sense, this is turning the VM on its head by allowing the pressures to only build up AT the lips, where the energy belongs. After all, the lips are our vocal cords, and for high notes, more energy is required, and conversely for lower pitches. The VM dissipates the breath energy to the chest and throat regions. Blowing TO the lips, places the energy squarely AT the lip where it's needed.

• Waste the air, more slowly for soft, in larger amounts for loud playing. I like to think of soft playing as a whisper or a gentle breeze and loud playing as a gushing fire hydrant. In any case, the airflow is free and quantitative (full), not compressed.

There are several techniques and breathing devices for developing this habit of respiration, but what I've described takes place regardless of the technique or device used.

There is an additional piece I would add that does not appear in any of the descriptions of this approach, that of the perceived tone quality. The compressed air flow tone sounds darker and more mellow to the player's ears, though tight and pinched and thin to the listener. The free-blown, quantitative approach to blowing results in a clearer, more ringing tone to the player, along with greater fullness. It's the clearer, more vibrant quality that is most evident to the player. However, to the listener, the tone is correspondently richer and fuller. This interesting paradox of tonal perception is not widely understood and often escapes the player's notice since the attention at first is given to the physical process and little to the product. I've found in my teaching that students more quickly develop the blowing habit once they discover the usefulness of creating a clearer product to their ears than they would instinctively wish to produce.

For a more detailed description of the VM in wind performance, check out the online article:

http://www.musicforbrass.com/articles/breathin.html

The article by Brad Howland is also posted with permission on Doug Yeo's website: www.yeodoug.com

You can also read more about the VM in the following books: Arnold Jacobs: Legacy of a Master by M. Dee Stewart (The Instrumentalist) Arnold Jacobs: Song and Wind by Brian Frederiksen (Windsong Press).

Windsong Press also sells the respiration devices that may aid the player in rediscovering the breathing efficiency possible.

http://www.windsongpress.com/breathing%20devices/Use_Devices.htm

Phil Norris is an Associate Professor of Music at Northwestern College, St. Paul, MN, where he teaches and actively performs on trumpet. The DMA was earned at the University of Minnesota. He is past president of the Christian Instrumentalists and Directors Assn. and is editor of the CIDA Sacred List of Instrumental Music.

Those of us who direct instrumental music programs often wish that our budgets could include hiring a professional "clutter cleaner" to organize our music libraries, beginning with our desk and the tops of our file cabinets! Our filing system is quite simple really. This year's concert music is on our desk in a pile. It is organized like an archaeological dig with last week's concert music closest to the top and last fall's concert music nearer the bottom. As for last year's music, well that is pile number two on top of the file cabinets... When a missing part mysteriously returns from a sabbatical often lasting years, we need only to call in an archive specialist from the Library of Congress to refile that part!

Here are several practical suggestions to organize the instrumental music library with the view to avoid piles of music, to save time, and to tap into the leadership potential of your group members.

Draw up a plan. Before organizing your library determine what your needs are. Decide whether to use vertical file cabinets, shelves, lateral file cabinets, or space-saving storage units such as those manufactured by Wenger Corporation. If you have to wait for budget approval to purchase file cabinets or storage units then begin organizing your library with shelving units. Determine whether you want to use envelopes or boxes to store each title, and how you are going to computerize information about each title. Decide how you will keep track of missing parts and how you will add new titles to your existing library. If you inherited a music library you may need to plan to reorganize those titles and absorb them into a new system.

Order supplies. Order the envelopes or boxes you will need, magic markers, pencils, a numbering stamp, a group name stamp, a stamp pad, yellow sticky memo paper, paper clips, and anything else you think you will need. Gamble Music Co. offers specialized music envelopes and filing boxes.

Recruit help. Once you have a plan and a sense of direction ask several members of your group if they would be willing to help you. In my experience every group has at least one or two members who are waiting to be asked to contribute their energies to an ongoing project. If your group uses a point system for grading offer to award these students volunteer points towards their grade. If you plan to meet on a Saturday morning make it a breakfast meeting with biscuits and coffee. Have goals for each work session and let the students actually do the work. After checking their work move through your task list item by item.

Use an Accession Number System. Do not alphabetize music by title within the cabinet or on the shelf. Instead of alpha order use an accession number system. Sorting alphabetically by title, by composer, and by genre can be done on the computer. Our pre-college orchestra music libraries work with three general categories determined by the instrumentation of a title: "O" designates full orchestra works; "S" designates string orchestra works; and "CE" designates chamber ensemble works. The first title in the orchestra category is assigned the letter/number designation of O-1. The next title in that category is O-2. As titles are added in a category each title receives the next available number. If a title takes up more than one box or envelope the letter/number designation is O-2a, O-2b, O-2c. This system allows additional parts to be added to titles as your group grows in size. As you enter a title into the computer this letter/number becomes one of the bits of information associated with that piece, along with the title, arranger/composer, publisher, genre, number of scores/parts, and a record of when the piece has been performed.

Keep track of missing music. This sounds so simple! It is actually very difficult, especially for large groups. Students need to understand that their directors and librarians will be relentless in the quest to locate missing music as a matter of good stewardship. Despite everyone's best efforts parts will disappear. Our librarians use a “Missing In Action" Sheet for titles with missing parts. This sheet has blanks for the title/composer/arranger/catalog/number/publisher information at the top. The rest of the sheet lists every possible score and part that could be missing from a set of orchestra music. As the music is refiled the librarians circle any missing parts on the sheet. At the bottom of the sheet they make notes about parts that should be erased or repaired. The music then is refiled (off the desk, off the file cabinets) and the MIA sheet is put in a folder. As music is returned throughout the semester the librarians refile the parts and cross off the missing parts on the MIA sheet. If at the end of the semester or school year missing parts have not been found then the librarians double check the sheets and leave them for the director to order necessary replacement parts. This system frees the director from the unending clutter of music that has not been processed.

Jay-Martin Pinner is the founding director of the Bob Jones Junior High and Academy Orchestras, having served as the conductor of the Bob Jones Academy Symphony Orchestra for 28 years. He is Head of the String Department at Bob Jones University and conducts the BJU Symphony Orchestra.

The young woman had a very rough past, involving alcohol, drugs, and prostitution. But, the change in her was evident. As time went on she became a faithful member of the church. She eventually became involved in the ministry, teaching young children.

It was not very long until this faithful young woman had caught the eye and heart of the pastor's son. The relationship grew and they began to make wedding plans. This is when the problems began.

You see, about one half of the church did not think that a woman with a past such as hers was suitable for a pastor's son.

The church began to argue and fight about the matter. So they decided to have a meeting. As the people made their arguments and tensions increased, the meeting was getting completely out of hand.

The young woman became very upset about all the things being brought up about her past. As she began to cry the pastor's son stood to speak.

He could not bear the pain it was causing his wife to be. He began to speak and his statement was "My fiancée's past is not what is on trial here.

What you are questioning is the ability of God to make new creatures of us. Today you have put God on trial. So, is God's forgiveness real or not?

The whole church began to weep as they realized that they had been questioning the grace of God.

Too often, even as Christians, we bring up the past and use it as a weapon against our brothers and sisters.

Forgiveness is a very foundational part of the Gospel. God forgives us, and all who call upon God."

"God, I ask you to bless my friends, relatives and email buddies reading this right now.

Show them a new revelation of your love and power. Holy Spirit, I ask you to minister to their spirits at this very moment.

Where there is pain, give them your peace and mercy. Where there is self doubt, release a renewed confidence through your grace. In Jesus' precious name. Amen

To see him walk across the stage one step at a time, painfully and slowly, is an unforgettable sight. He walks painfully, yet majestically, until he reaches his chair. Then he sits down, slowly, puts his crutches on the floor, undoes the clasps on his legs, tucks one foot back and extends the other foot forward. Then he bends down and picks up the violin, puts it under his chin, nods to the conductor and proceeds to play.

By now, the audience is used to this ritual. They sit quietly while he makes his way across the stage to his chair. They remain reverently silent while he undoes the clasps on his legs. They wait until he is ready to play.

Instead, he waited a moment, closed his eyes and then signaled the conductor to begin again. The orchestra began, and he played from where he had left off. And he played with such passion and such power and such purity as we had never heard before. Of course, anyone knows that it is impossible to play a symphonic work with just three strings. I know that, and you know that, but that night Itzhak Perlman refused to acknowledge that. You could see him recomposing the piece in his head. At one point, it sounded like he was retuning the strings to get new sounds from them that they had never made before.

When he finished, there was an awesome silence in the room. And then people rose and cheered. There was an extraordinary outburst of applause from every corner of the auditorium. We were all on our feet, screaming and cheering, doing everything we could to show how much we appreciated what he had done. He smiled, wiped the sweat from this brow, raised his bow to quiet us, and then he said, not boastfully but in a quiet, pensive, reverent tone, “You know, sometimes it is the artist's task to find out how much music you can still make with what you have left."

What a powerful line. It has stayed in my mind ever since I heard it. And who knows? Perhaps that is the way of life-not just for artists but for all of us. So, perhaps our task in this shaky, fast-changing, bewildering world is to make music, at first with all that we have and then, when that is no longer possible, to still make music with all that we have left. Source Unknown

When I was quite young, 6 or 7 years old I think, my dad would work on his car in the garage. Sitting near the kerosene heater was an old upright grand player piano. The “player” parts did not work, in fact I think that machinery had been removed even before Dad obtained the piano. I had a couple of choices: I could watch him work on the car, and perhaps get an early start on an illustrious career as a mechanical engineer, OR, I could get interested in that monster of a piano with the black and white teeth all across its face.

In between changing spark plugs or adjusting brakes, Dad would sit down at the piano and plunk out a simple tune. He really wasn't a pianist at that time; trombone was his instrument. But he did have a great musical ear and his key-pecking fueled my imagination at the possibilities of sounds even from that old clunker of a piano.

I was about 9 when I first went to see Mrs. Vosburgh, who would become my piano teacher for the next ten years. She taught me to read, to have some semblance of discipline in practicing, and gave me a solid exposure to the standard piano literature.

My parents bought a beautiful blonde-colored spinet piano (which is still my favorite spinet today) and after a couple of years of lessons, I began to get restless.

Dad played in the community band as well as other groups and I wanted to be a part of that as well. He bought a saxophone for me from my aunt, and I aggressively practiced it so I could be a part of the school band. I relished the world of music. Later Dad bought me a clarinet. And still later, I learned trumpet and then eventually played trombone in high school marching band.

But since you have read this far, let me step back and explain the “ear training” experience.

When I was about age 11, my dad began to get more serious about playing the piano. He bought a chord chart and a “fake book” of popular songs and began to practice every night for an hour or two after my bedtime. Trouble was, the piano was in the living room just outside my bedroom door, and I couldn't sleep knowing he was learning some new facet of music that I wasn't getting in my lessons! I sensed a new door of adventure opening. Music was becoming almost a living thing with its own personality, with its own innate rewards. I felt I was on the threshold of a whole new universe of creativity…So…I listened.

Essentially, this was a huge part of my ear training. I don't know if Dad ever realized how significant this was in setting my foundations for music. When I came to Michigan State as a music education major, I passed off two years of formal ear training and was by that time, playing and improvising “by ear.”

The moral of the story is: start where you are standing…never stop being inquisitive. Dad had very little formal training in music, but he made a lot out of what he had. He paid for my music lessons, but he also awoke my creativity and trained me in the ear training skills so necessary for a composer or arranger. This was always an encouragement, a legacy that he has left me and other family members for which I will always be grateful.

Dale Everson went to be with the Lord on Jan 4, 2006

Dana Everson has over 100 published works. He holds the BME and Master's in Saxophone Performance degrees from Michigan State University and a Master of Sacred Music from Pensacola Christian College. Everson currently teaches at Northland Baptist Bible College in Dunbar WI. Wisconsin

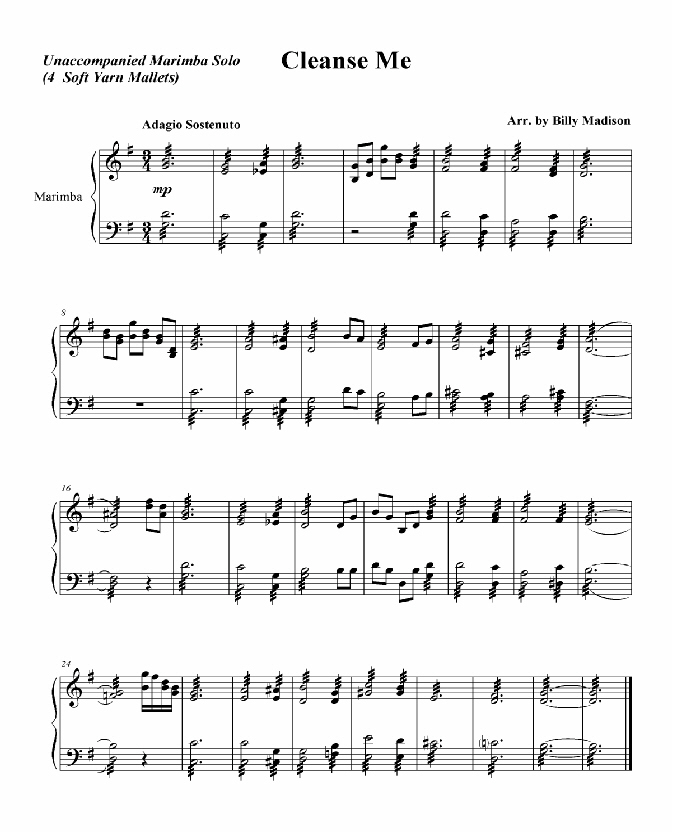

Billy Madison has taught instrumental music in the Arkansas Public Schools for 18 years. He holds both the BME in Instrumental Music and the MM in Music Theory and Composition from Arkansas State University. He studied composition with Jared Spears and Tom O'Connor. Madison has played percussion with the Delta Symphony since 1978.

The “Doctor” consists of two parts. Part I is entitled “Klug's Clarinet Calisthenics;” Part 2, “The Clarinet Doctor Teacher's Manual.”

Any serious clarinetist ought to, and certainly all clarinet teachers should own this book!

Part I begins with an Introduction followed by a listing of Klug's studio curriculum. Technique studies, etudes and solos are listed for each semester of the Undergraduate Clarinet Curriculum.

There follows an Undergraduate Jury Exam schedule for each of the eight semesters of clarinet study.

A thorough discussion of practicing follows together with a practice planning guide.

Klug presents a plan for acquiring technique which would not fail to produce impressive technique if the practice guide is carefully followed.

Alternate scale fingerings, articulation studies, break-crossing/thumb exercises, scales (including Bebop scales), triad exercises, broken scales, dominant 7th arpeggios, diminished 7ths, scales in 3rds and 6ths, and on and on.

Part 2 begins with a thorough discussion of clarinet embouchure, breathing, body posture and hand position.

The tongue and throat are then given attention with corrective advice and suggestions to students. The section concludes with “Fixing an Under Sound.”

Tips for Tonguing are included also, of course.

Several pages are devoted to discussing the adjusting of single reeds. Next the reader is given instructions for making single reeds including the equipment which will be needed. Other available printed sources on the subject are listed.

For teachers the “Tips for Private Teaching” section is worth the price of the book.

An interesting section on Squeaks provides information on their causes and corrective measures to eliminate squeaks.

Very helpful information about the Bass Clarinet is included along with preparing for an orchestra audition.

A elect, annotated list of precollege clarinet solos provides the reader with some valuable literature possibilities.

The five-page treatise on teaching musicality is excellent. It begins, “Many people believe that to play musically, one must start early in life to play a musical instrument, practice diligently and be blessed with innate talent. To be sure, having control of two of the three essential elements isn't bad, but not possessing that great genetic code doesn't necessarily doom the majority of us to be unmusical.” (p. 107) Klug discusses tempo, rubato, pickup notes, appoggiaturas, shaping notes, register projection, connecting intervals, expressive accents and phrasing.

A list of Additional Pedagogy Publications by Howard Klug concludes the book.

It is difficult to conceive of 117 pages including more valuable information than does “The Clarinet Doctor!!” Perusing a few pages causes one to realize that “The Doctor is Indeed IN!”

Harlow E. Hopkins is Professor of Music, Emeritus, Olivet Nazarene University, Bourbonnais, Illinois, and continues there as Adjunct Professor of Clarinet. He holds the D.Mus. from Indiana University, Bloomington.

The Publishers' Space

The Brass Space

The String Space

Thinking...

Make Do With What's Left

The Lone Arranger's Space

The Percussion Space

The Woodwind Space

And As A Last Resort

Use Words.

St. Francis of Assisi

by David E. Smith

Something for everyone is our goal with over 5,000 pieces now available

by Phil Norris

On the other hand, the VM creates increased blood pressure that can lead to bursting air sacs in the lungs, strokes in the brain and windpipe constriction or apneas.

by Jay-Martin Pinner

From Filing to Photocopying and the Future - Part 1

by Harlow E. Hopkins

But this time, something went wrong.

Just as he finished the first few bars, one of the strings on his violin broke. You could hear it snap-it went off like gunfire across the room. There was no mistaking what that sound meant. There was no mistaking what he had to do. People who were there that night thought to themselves: We figured that he would have to get up, put on the clasps again, pick up the crutches and limp his way off stage, to either find another violin or else find another string for this one. But he didn't.

by Phil Norris

The moral of the story is: start where you are standing…never stop being inquisitive.

Sometimes I would get up, poke my face out the door, and he would say “Oh, all right…you can watch for a few minutes.” That meant I could look at the music, the chord chart, and his hands as he meticulously, painstakingly formed and reformed the music with his ear as his main guide. After 15 minutes or so, I was sent back to bed, but …I continued to listen. I formed the chords and the melodies in my mind and the next morning before school I would try out what I had remembered. I also began attempting to write out some of the sounds. (I think I kept the local music store in business by buying reams of music manuscript paper!) This pattern continued for several months.

by Billy Madison

by Harlow E. Hopkins

In this issue Howard Klug's The Clarinet Doctor will be reviewed. It was published by Woodwindiana, Inc., in 1997. Howard is Professor of Clarinet at Indiana University, Bloomington. (hklug@indiana.edu)