| |

[NEWSLETTER of DAVID E. SMITH PUBLICATIONS, LLC] NEWSLETTER of DAVID E. SMITH PUBLICATIONS, LLC

NEWSLETTER of DAVID E. SMITH PUBLICATIONS, LLC

VOL 8, NO 4, WINTER, 2006

© 2006 Copyright of David E. Smith Publications

All Rights Reserved. Made in U.S.A.

Table of Contents

The Publishers' Space

The Lone Arranger's Space

The Brass Space

The Strings Space

The Woodwind Space

The Percussion Space

Brass Bands In Britain >

To Table Of Contents

THE PUBLISHER'S SPACE

by David E. Smith

To You, thanks for the patronage in the past several months that has resulted in increases in our sales and services-some of them to record levels. We are most grateful for that in a time when much of the music industry is suffering terribly.

We look forward to continuing to strengthen our offerings, services and efficiency for all those searching for quality, sacred instrumental music.

By the time you receive this issue of Lines And Spaces® we should have the new version of www.despub.com up and running. Some of the highlights of this revision will be catalog, newsletter and search capabilities. Areas such as the "What's New," "Dealer Lists," "Conventions & Exhibits," "Catalog request" and other order forms will have pretty much the same features and functions.

In using the "View catalog" there will be search capabilities quite similar to our sister site of www.churchmusic.biz. The two major enhancements will be the inclusion of all our publications, distributions and some other publishers which will double the number of product offerings. Also, the Appendix, and additional comments as well as sound files, will be integrated into the "View Catalog" page design.

In the "Newsletter" area you will now be able to search any word or phrase of your choosing. A highlighting feature will draw up your search throughout all newsletters and even the entire web site. We will have to do some editing to this page so be patient with us. We will likely add the index of topics feature back in as a bonus (aid.)

We continue to optimize the www.despub.com site so you will find it coming up in the top of your search engine's lists as you search for sacred instrumental music and related topics.

David E. Smith Publications, LLC is pleased to offer new brass and woodwind works for Christmas by Dana F. Everson. God Rest Ye Merry Gentlemen is a flute solo at level four, accompanied by piano. This exciting arrangement can be had for only $4.50. Carol Of The Bells is a clarinet solo at a level three and is accompanied and priced at $4.50. He Is Born The Divine Christ Child presented as a woodwind quartet and is accompanied by piano-the wind parts are for two flutes and two clarinets. It is level three and priced at $9.00 for score and parts. If you need something for trombone quartet or low brass quartet, then O Come, All Ye Faithful might just do the job. It is scored for four trombones, but does include a horn part for first trombone as well as baritone horn treble clef parts for the third and fourth trombone and tuba on part four. This level three arrangement comes with score and all parts and is priced at $7.00.

Angels We Have Heard is a brass trio at level three. The set comes with score and brass parts of trumpet part one, horn and trumpet for part two, trombone and baritone horn treble clef for part three. This piece incorporates an integral piano part as well. Price- $9.00.

And finally for brass quartet-Ding Dong Merrily On High at a level three. The full set is priced at $12.00 and includes parts for two trumpets, horn and trombone (with baritone horn treble clef) as well as an integrated piano part.

Also, by Monty J. Budahl, are individual works for brass quartets that come with score, two trumpet part, two trombone parts, optional French horn and baritone horn treble clef for the trombones and price at $9.95 per set. Trust and Obey at level 2.5 (#145437); The Early Patriot's Medley at level 2.75 (#145439); Faith Is The Victory at level 2.75 (#145440); and Go Ye Into All The World at level 3 (#145438.) You can get these pieces in collection as well. Two new collections are now available incorporating new works as well as replacing previous publications-Sacred Brass Quartet Collection #145422 and Christmas Brass Quartet Collection #145423 are soon to be discontinued.

New is Sacred Brass Quartet Collection Vol No.1 (#145435) which includes arrangements of: A Shelter In The Time Of Storm, Lead Me To Calvary, Nothing But The Blood, Trust And Obey, Faith Is The Victory, Angels We Have Heard On High, Hark, The Herald Angels Sing, It Came Upon A Midnight Clear, and, O Little Town Of Bethlehem. Sacred Brass Quartet Collection Vol No.2 (#145436)will include: Jesus Paid It All, Come Thou Fount, Near The Cross Medley, Go Ye Into All The World, The Early Patriots Medley, Saints Bound For Heaven, and Come Ye That Love The Lord.

You can find more information on these and other fine arrangements on www.despub.com and www.churchmusic.biz.

Preach Christ Always

And As A Last Resort

Use Words.

St. Francis of Assisi

To Table Of Contents

THE LONE ARRANGER'S SPACE

by Dana F. Everson

Self-Learning Projects for the Energetic Writer-Part II

In the previous article I made a few suggestions for the energetic writer who wants to increase his experience in writing but may have limited opportunities for formal training. I once asked Dr. Alfred Reed the question: “How does one learn to compose?” to which he replied: “Take a large pencil with a large eraser [computer program, etc.] in one hand, and with the other hand, grasp the seat of your trousers and place them firmly on the chair, and write, write, write!”

Here are a few more suggestions for self-learning projects…and don't forget the large eraser.

Take a choir arrangement and attempt to add 1-3 instrumental parts to the accompaniment. You are not necessarily ADDING to the arrangement, but looking for those places where, let's suppose, the color of a trumpet along with the piano would add a little more interest or impact. Use the new instrument sparingly, because the original arrangement was not conceived for the instrument(s) you are adding.

Rewrite the piano accompaniment of a choral arrangement for a small instrumental ensemble. Be careful not to overwhelm the voices, but try to maintain the original “message” of the piano accompaniment. By transcribing accompaniments by capable arrangers you will learn a great deal about writing appropriate supports for vocal and instrumental solos/groups.

Pick 3 or 4 of Bach's Two Part Inventions and transcribe them for as many combinations of instrumental duets as possible. I would suggest Inventions # 4 in d minor, #8 in F major, and #13 in a minor. These will greatly challenge your thinking about using counterpoint in your arranging.

Take a characteristic arrangement, something close to what you would like to do and copy the score for your own learning. I remember admiring Harold DeCou's brass sextet arrangements. Actually, it was the playing a couple of those pieces with some of our church musicians that first got me excited about attempting to write for brass ensembles. Years later I was able to sit down with Mr. DeCou and have a “private lesson” with him. I was so encouraged by his comments and suggestions, and I think he appreciated knowing that his writings had motivated me in that area.

Explore each instrument, including the more unusual ones, by writing short solos, duets, or trios for them. I have always said it was the E-flat trumpets in the Michigan State University Marching Band under Bill Moffit that drew me to study there for five years and two degrees. There was a unique color in those instruments which capped off the massive brass and percussion sound that captivated me.

In another “private lesson” setting I expressed to Dr. Moffit how curious I was about the “E-fers” as we called them. He said most people try to write too high and too often for them. I have learned to use their sound a little on the sparing side, saving them for climactic and color-intense effects. Other not-so-common-instruments can benefit from that same advice.

I hope these ideas will stimulate further ideas for your self-learning toolbox!

Dana F. Everson holds the BME and Master's in Saxophone Performance degrees from Michigan State University, and a Master of Sacred Music from Pensacola Christian College. He has over 300 published works.

To Table Of Contents

THE BRASS SPACE

by Phil Norris

When it comes to tuning, musicians can become slaves to a tuning device or the piano. Yet, when tuning with instruments capable of varying pitch, tuning to the piano or tuner will not be in-tune. To play in-tune with winds and strings, tuning must be done according to the tuning produced by the harmonic series of the chord root, what is called Harmonic Tuning (hereafter HT) or aka Natural Tuning. For example, if players are forming the notes of an A major chord, the HT frequencies would be the following:

Root: A-440 C#-550 E-660

The problem with electronic tuners based on the piano's equal temperament (ET) tuning, the frequencies of these notes are (approximately):

A-440 C#-554.37 E-659.26

In HT, when the tones are combined, additional tones (known as Resultant Tones, RT) are created that are the arithmetic difference of the frequencies played. For example, when C#-550 and A-440 sound together, another pitch, A-l 10 (550 minus 440), is created. This RT (A-l 10) is precisely two octaves below A-440. When E-660 and A-440 sound together, RT A-220 is created.

If the equal-tempered C#-554.37 is combined with A-440, the RT will be 114.37, which is not quite A-l 10. Thus, the richness of tone is diminished since 114.37 does not align with A-440 as does A-l 10.

Part of what makes sound beautiful is perfect or near-perfect intonation which will include the presence of resultant tones. So, in order to get the most resonant ("rich") tone, tuning must be done to the harmonic series, whether instrumental or vocal.

What does this mean in terms of tuning chords? To save time, I'll summarize the HT compared to ET tuning for each interval within the octave. By working with the frequencies of HT versus ET, the following is a summary of how players should adjust pitch compared to equal temperament (piano or tuner) frequencies. The chart shows the degree of change from ET in cents (c.). A cent is 1/100 of a half step (e.g. 5c. would be 5% of a half step, only a very slight change from equal tuning but still significant in how the interval or chord will sound).

You can also see that the Inversion of a given Interval (e.g. M3 and m6) have inverted tunings. The M3 interval is tuned 14c. lower than ET and the m6 interval is tuned 14c. higher. This tuning is perhaps opposite of our natural instincts. We might think that if we play the 3rd of a major chord that we would tune the 3rd somewhat sharp, but the opposite is the case.

| Interval |

HT cp. to ET |

Interval |

HT cp. to ET |

| Minor 2nd (m2) |

12c sharp |

Major 7th (M7) |

12c. flat |

| Major 2nd (M2) |

4c. sharp |

Minor 7th (m7) |

4c. flat |

| Minor 3rd (m3) |

16c. sharp |

Major 6th (M6) |

16c. flat |

| Major 3rd (M3) |

14c. flat |

Minor 6th (m6) |

14c. sharp |

| Perfect 4th (P4) |

2c. flat |

Perfect 5th (P5) |

2c. sharp |

| Aug 4th (A4) |

10c. flat |

Dim 5th (d5) |

10c. sharp |

When playing chords, the intervals we encounter most are Roots, 3rds and 5ths. If we tune to ET, the resonance of the chord will be "nervous" sounding because of the lack of aligned pitches and the RTs. If we tune using HT, there is a fullness, a "relaxed" quality to the sound because of the aligned chord and RTs. This means that players must know which note of the chord they are playing: root, third, fifth, or seventh. For major chords, roots and their octaves are tune pure (i.e. 2:1 frequency ratios), 3rds are tuned 14c. low compared to ET, 5ths are tuned 2c. high compared to ET.

For minor chords, the 3rds are tuned 14c. high compared to ET. If you are not accustomed to tuning this way, it may take some getting used to, but the rich, relaxed quality of the HT chord is very rewarding, not to mention sounding in-tune for us and the listener!

This is best practiced with one other player of the same Instrument, but instruments of similar timbre will produce audible RTs, particularly as you play higher (treble instruments RTs will be more easily heard than bass clef instruments). Play both 3rds and open 5ths to produce the RTs. A third player to complete the triad will certainly help in experiencing HT.

One question remains, what does a player do when accompanied by the piano or some other fixed-pitch instrument? In this case, it makes sense to tune to the fixed instrument unless that instrument is playing a single tone. This is probably better done instinctively than consciously (i.e. just listen). But in wind or string ensembles, HT is the norm.

I'll close with the story about when I first experienced this. During my first term at Northwestern University, Dale Clevenger, principal horn of the Chicago Symphony, was conducting a master class. On stage were four horns.

At one point he stopped the quartet and asked the two playing the root of the chord in octaves to play. It was perfect. Then he asked the player with the 5 of the chord to join the first two, again in-tune. Finally he asked the player on the 3rd to play. The chord was nervous and unsettled sounding. He stopped everyone and asked the player on the 3rd to keep lowering the pitch at his direction. They all played again, and as Mr. Clevenger pointed downward, the player lowered the pitch; Clevenger kept pointing downward over several seconds.

I thought that the chord would become minor at any moment, the pitch of the 3rd dropping as it was. When the HT was reached the chord "relaxed" and had a rich sonority. I was amazed at how low the third was, but only because my tuning sense had been oriented to ET. I never forgot that aural lesson.

Later I came across some articles that explained the math, and it all made sense. God has made the world of sound consistent with math, but in music the math is made beautiful.

If you want to dig into this deeper, here are some websites that will do that for you (the first one listed is of historical interest and perspective as well as musical value):

http://www.lq/legann.com/histune.html

http://www.kylegann.com/tuning.html (with fascinating audio examples)

http://www.alphaentek.com/rlc/harmony.htm

http://tnembers.aol.com/chang8828/tuning.htm

Phil Norris (DMA, Univ. of Minnesota) is professor of music at Northwestern College in St. Paul. He is past president of CIDA. He is also a musician, teacher and elder in his local church.

To Table Of Contents

THE STRINGS SPACE

by Jay-Martin Pinner

Organizing the Church/School Instrumental Music Library-From Filing to Photocopying and the Future - Part 3

In the last two columns we discussed setting up and running the day-to-day operation of an instrumental music library. This column will focus on photocopying and several observations about the future of instrumental music libraries.

What about photocopying? The current copyright laws, while not perfect, attempt to strike a balance between protecting “fair use” of creative property and protecting the creator and/or owner of such property. As instrumental directors we are in a unique position to influence future generations of musicians to obey the spirit as well as the letter of the copyright laws. We are responsible to familiarize ourselves with copyright law and to set an honorable example for our students and colleagues.

To determine whether a photocopy is legal directors need to ask themselves one question: “Is this photocopy depriving the copyright owner from a sale of this work?” If the answer is “yes,” then the photocopy is illegal. To copy illegally constitutes stealing from both the copyright owner and the creative producer because no royalties are paid for the illegal copy. As believers we would not tolerate someone stealing money from us or our church, school or business.

As instrumental directors we steal money from publishers, composers and arrangers regularly. We attempt to justify our actions with excuses such as: “Our budget is too small to order more parts;” or “That company is so big they will never miss a few dollars;” or “It's for a good cause.” We are trying to have high music standards for our group and so much good music goes out of print.”

Practically speaking photocopies may legally be made only for the following reasons:

- Music may be photocopied in an emergency situation for an imminent performance provided the music is destroyed and reordered immediately after the performance.

- Music may be photocopied to facilitate page turns.

- Music may be photocopied if the piece is out of print and the user obtains written permission from the publisher. The publisher usually charges a small fee for such permission. This also applies if a group owns a title that has become a “rental-only” piece and the group needs to procure additional parts.

When photocopies are made and distributed to a group the director should let the group know why the copies were made and why they are legal. Such an announcement reminds the group about the importance of complying with copyright laws and that the group takes such compliance seriously.

If a director inherits an instrumental music library containing illegal photocopies it is imperative that those copies be paid for or shredded. Librarians should be advised to systematically go through all music holdings and inform the director about photocopies.

When a group secures permission to photocopy parts two copies of the permission should be kept on file. One copy should be placed with the music in its folder or box. The other copy should be placed in an administrative file.

More copyright information may be found in the pamphlet Copyright: The Complete Guide for Music Educators, by Jay Althouse, available from Alfred Publishing Co., Inc.

What about the future? The future is already here! Technology is enabling music publishers to allow directors to download and print music directly from the computer, and photocopy as many parts as needed for one all-inclusive fee. Other advances are allowing publishers to print on demand rather than keep large inventories of music. When a director orders a piece of music the publisher prints it out and ships it. Inventories may become obsolete.

One of the most unique and promising tools for helping instrumental groups to manage a music library is the MusicPad Pro™, a tablet sized digital sheet music reader (www.freehandsystems.com). This touch screen, backlit, color display features remote page-turning capability, add/erase features for rehearsal marks and annotations, and 4 lb portability. Over 85,000 scores are available for downloading and your own music library may be scanned and stored on the MusicPad Pro™.

Like most new emerging technologies the $1,199.00 per unit cost for this paperless music is prohibitive. As the price decreases however groups will find ways to take advantage of the convenience and flexibility of this new instrumental music library.

It might not be long before instrumental students will take home a computer music tablet along with their laptop computer! At that point our budget requests will have to include lockable music tablet storage cabinets…

To Table Of Contents

THE WOODWINDS SPACE

by Eric H. Larson

The study of the oboe is full of traps for the student, and he must deploy great perseverance in order to arrive at a clean execution and attain a certain facility. As much as the tone of the oboe can be soft and velvety (albeit a little nasal) when in the hands of a skilled virtuoso, it can be sour and screeching when the player is inexperienced or lacks the taste of a true artist. (Pierre Larousse, from the 1866 Grand Dictionnaire Universel)

These words are just as relevant today as when they were first published 140 years ago. Fortunately, there are some considerations regarding embouchure which can help bring the thoughtful oboist closer to Pierre Larousse's ideal of the “skilled virtuoso.”

A cornerstone of effective modern oboe tone production is a “round” embouchure. The lips must surround the reed, as if whistling or drinking out of a straw. This creates a soft cushion for the reed to rest in, reducing edge in the sound and warming it up. At the very least the oboist should avoid the opposite: a “smiling” embouchure. When players pull back the corners of their mouths in this way, they are working against themselves because the lips are stretched flat. With very little cushion for the reed, it will likely produce any number of undesirable tonal characteristics. In addition, inexperienced and self-taught oboists often struggle with the chin muscles directly below their lower lip. It is critical that these chin muscles stay flat and relaxed, as otherwise the reed will not vibrate properly.

If a player initially struggles with this, it may help to think about pointing those muscles down (like a clarinet embouchure) in order to train them. The chin should never “bunch up” so that multiple small dimples form. Complicating this matter is that there are two different styles of American bassoon embouchure, one of which intentionally pushes these chin muscles up against the reed. A young or inexperienced oboist may see a bassoonist doing this and imitate it.

Just as round embouchure is important for good tone production, a flexible embouchure is important for overall playability. The oboist must move and adjust the embouchure for the different ranges of the instrument, as (in theory) every note on the instrument has different requirements.

Ideally, these embouchure adjustments are rather subtle. In practice however, one or more may need to be exaggerated in order to compensate for an inadequate reed or a poor or damaged instrument. The flexible nature of the oboe embouchure can be reduced to three principles. The first two of these principles are basic and apply to all oboists. The third is somewhat more advanced, which a player will begin to become more aware of as they progress in their mastery of the instrument.

1. Variable lip pressure on the reed (a “biting” action): this is the basic support for the reed. Students of all reed instruments are told early on in their education, “Don't bite!” Unfortunately this may lead to a misunderstanding of how to support and control the oboe reed. If the player doesn't “bite,” it will be virtually impossible to control the vibration of the reed, to play with some semblance of intonation, and to create a seal with the lips that doesn't leak air. Rather, the player should be cautioned not to bite so much that the reed isn't able to vibrate properly.

Excessive “biting” pressure will result in a thin tone which is weak in upper harmonics and will almost invariably result in sharp pitch throughout the range of the instrument. The teeth - where the “biting” pressure comes from - should provide the lips with relaxed, comfortable support. If the oboist can feel indentations on the inside of their lips after playing, they are using too much pressure or “biting too much.” If these indentations are present, it is possible that the player may be using an inappropriate reed for their experience level and ability. Unfortunately in this situation, using this kind of excessive pressure may be the only means by which the reed and instrument can be controlled.

2. Variable amount of reed in the mouth: when the player's reed and instrument are in good condition, proper breath support is utilized and all other elements of good embouchure are correctly executed, the appropriate amount of reed in the mouth is the most important remaining factor effecting tone quality and intonation.

In general, the player should use as little reed as possible while still being able to produce a full tone that is in tune. The oboist should be encouraged to experiment with ever smaller amounts of reed “inside” of their mouth. This will initially result in a loss of control and the player may resist playing this way. However once the technique is mastered, it will result in much greater control, more reliable attacks, greater dynamic capability and greater capacity for color change.

While experimenting with less reed in the mouth, the player should not allow the lips to be drawn out in front of the teeth into a kind of “puckered” position. The muscles around the lip area are some of the weakest in the body, and without the teeth to support them the player will have very limited control over the reed and instrument.

3. Variable downward pressure on the lower lip: gentle downward pressure on the lower lip is a phenomenon which naturally occurs while playing the oboe due to the design of the instrument. Except when using a few obscure alternate fingerings, at least one finger of the left hand is always in contact with the oboe. Therefore, additional downward pressure can be created whenever desired, with the reed being pressed down into the player's lower lip.

In general, the higher the note the more benefit there usually is from additional downward pressure, as it allows for a more open embouchure while still controlling the reed and playing in tune. This gentle downward pressure supplements other embouchure and breath support elements and should always act as a subtle, secondary control element.

If at any time the player removes the reed from the mouth and the cane appears bent, far too much pressure is being applied with the left hand.

In brief, when an oboist becomes comfortable with the use of a round and flexible embouchure, intonation, playability and tone cannot help but improve. The player will no longer be hindered by self-imposed limitations. The ability to play the instrument will develop at an accelerated rate, and place the soft and velvety character which Monsieur Larousse so praised within reach.

Eric Larson is currently principal oboe for the Chicago 21st Century Music Ensemble and the Oak Ridge Symphony and is a faculty member of the University of West Alabama. His primary instructors have been Ralph Gomberg (Emeritus principal oboe, Boston Symphony Orchestra), Ray Still (former principal oboe, Chicago Symphony Orchestra). He has played under Seiji Ozawa, Vaclav Nelhybel, Louis Lane, and several others.

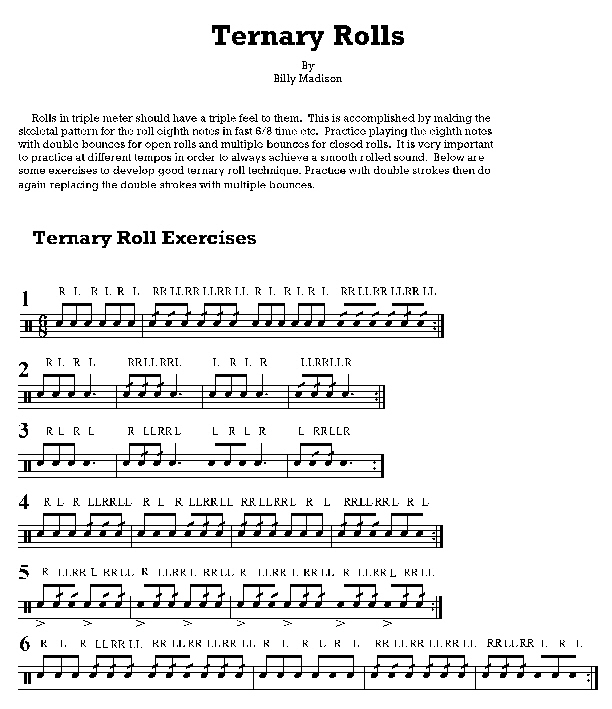

THE PERCUSSION SPACE

by Billy Madison

Billy Madison has taught instrumental music in the Arkansas Public Schools for 18 years. He holds both the BME in Instrumental Music and the MM in Music Theory and Composition from Arkansas State University. He studied composition with Jared Spears and Tom O'Connor. Madison has played percussion with the Northeast Arkansas Symphony since 1978.

To Table Of Contents

To Table Of Contents

BRASS BANDS IN BRITAIN

by Douglas Smith

OVERVIEW

To use a year's sabbatical leave to study amateur brass bands in England was greeted by amused curiosity. “What is there to study? Other than trombones the instruments all have three valves, and so do the brass instruments in America.

Nearly all the music is written in treble clef. That may be worth a look, especially for trombones and tubas, but bright players could figure that out fairly quickly. Besides, none of the players are professional, and we have plenty of amateurs in the schools right here at home. Who would want to spend that much time and go that far just to listen to amateurs playing brass instruments?”

With the question comes a large part of the answer: Amateurs in Great Britain are indeed playing brass instruments, and they are continuing to play-joyously and enthusiastically-well into adulthood. Of course an ulterior motive here was to find psychological clues, not so much to import brass bands, but rather to plant the joy and enthusiasm with worship-contributing church orchestras here at home. The assumption here is that elements that work for the English should also work for the Americans. (The 11 chapters listed below will appear in Lines and Spaces in the order shown)

1 The Aldbourne Band

2 Instruments

3 The Sound

4 Social Implications

5 Economic Realities

6 Conductors

7 The Section System

8 Literature

9 The Adjudication Process

10 Salvation Army Cross Currents

11 Epilog

Part 1THE ALDBOURNE BAND

“By the way,” said the professor who was coordinating the Sounding Brass Workshop. “We are planning to take a van to Friday evening's rehearsal of the Aldbourne Band. Let us know if you want to go.”

Of course we wanted to go! When we arrived at the modest building the band called home, the members were already hard at work, and even though they rarely had visitors at their rehearsals, they did not seem to be the slightest bit distracted. We thought that these small town brass players would be intimidated when they found out about all of our advanced university music degrees, but we soon found out that they were not the least bit impressed by such trivialities.

The Rehearsal

There were warm, welcoming vibrations from conductor, players, and family members who had come to bathe in the sweet brass sounds, but the players were completely involved in doing what they loved best-making music.

One of our group pointed toward a lad who looked to be a prime candidate for 5th grade beginner band. Strictly business, this imp of a cornet player did not seem to have the slightest problem pulling his weight in the 3rd cornet section. We learned later that he was a very younglooking 13.

“Do the young ones play all the concerts and contests?”

“All the concerts, yes. In contesting each band can only bring 25 brass players plus percussion, so we have to cut out 5 or 6 from our regular number. They always go along and support us, but they don't play.”

The Conductor: Don Keene

Midway through the rehearsal the band took a break, and we had a chance to talk with conductor Don Keene. One thing that was already obvious was his stutter. Often his directives took three, four, even five attempts before totally emerging, but the group always waited patiently and did what he asked.

“How long have you conducted this band, Mr. Keene?”

“I have been the head conductor for 10 years, plus 9 years as deputy conductor. This band was formed around 1830 and I am only its 7th conductor.”

“Incredible! This must be a very good paying job to keep fine conductors such a long time.”

“We have had fine conductors, but it certainly is not because of the pay. There is no pay. I work for British Railway-testing diesel engines. Most days I take my music scores to work with me and study during running-in periods, tea breaks, etc. Also I do some arranging and work out concert programs. This way I did my three years' national service in the Band of the Royal Horse Guards, and also played as a State Trumpeter. That was a long time ago.”

“Did you ever consider staying in the military and making a career of it?”

“No. The attitude of many of the older military bandsmen was 'How much do we get paid, and what time do we finish?' Not for me!”

The “Championship Section”

Even though it represented a rather small town, it was categorized in the very highest, or “Championship Section.” We wanted to know, “Has the band always been in the Championship Section?”

“No. Only about 20 years ago we made it to the top section. We had to work our way up. That was actually the first year I came as deputy conductor.”

Musical Training

“Tell me about the training your people get. Have they all studied privately?”

“When a lad wants to be in the band he gets one of our players to teach him. We do have a boy's band, and the ones who rise to the top can come and play with us when we feel like they're ready. We have a few that play with both groups. You know what they say: 'If you expect to grow mighty oaks, you have to plant some acorns.'”

“Do any of your people go into music professionally?”

“Our solo trombone is now at the Royal Academy of Music in London. I actually taught this lad free of charge, but now, after two years at the R. A. M., we think his playing does not fit us anymore. We have a cornet player as well who is studying to be a trumpet professional.”

The Players

After the men resumed their seats Mr. Keene invited us to ask questions. Already having discovered the youngest member, one of the guests wanted to identify the oldest. A baritone player said he had begun playing in the group 55 years. The tuba player right behind him chimed in to say that he was the only one left that remembered the band before his friend arrived. These two men had a combined tenure of 111 years, and neither had any plan to retire.

After our discussion with Conductor Keene, we knew that nobody made a living playing an instrument. So we asked them, “How do you support yourselves?”

Around the room came the replies: “Electrical engineer,” “Railway coach builder,” “Car salesman,” “Leather working apprentice,” “Bus driver,” Night watchman,” “Blacksmith,” “Computer chip designer,” “Newspaper editor.” No college professor, high school band director, staff arranger, church musician, or even music store manager. For these exhilarated devotees the word “music” meant only one thing: The Aldbourne Band.

As they started into their final period of rehearsal, one of the visitors sat down beside a rather attractive blonde lass who identified herself merely as “Sue.”

“Are you related to one of the bandsmen?”

“Not yet,” she said. “I am the fiancée of the 4th chair Bb cornet player. We are getting married next summer.” “How do you think you will feel being married to a bandsman?”

“I didn't think I would like it at first, but after two years of going to all the rehearsals and concerts I enjoy it very much. I almost wish I could play!”

Douglas Smith is a Professor of Church Music at The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, Louisville KY, where he has taught since 1975. His arrangements for various instrumental combinations have been published by DESPUB, Broadman Press, Theodore Presser, Lorenz, Hope Publishing Co., and several others. He holds the B.S. degree from Carson-Newman College, the M.M.E. from the University of North Texas and the D.M.A. from the University of Michigan.

Order Newsletter

[top]

|

|

|

|